What is NAT? Understanding Types of NAT Made Simple

What is NAT?

Network Address Translation (NAT) is a technique used in networking to map private IP addresses to public IP addresses. This allows multiple devices on a private network to share a single public IP address when accessing the internet. NAT is commonly implemented in routers and firewalls to conserve public IP addresses and add a layer of security by hiding internal network details. In simple terms, NAT acts like a translator between your home or office network and the vast internet, ensuring your devices can communicate without needing a unique public IP for each one.

Why Use NAT?

IP Conservation: With the limited pool of IPv4 addresses, NAT helps by reusing private IP ranges. Security: It hides internal IP addresses from the outside world, reducing direct exposure. Cost-Effective: Sharing a single public IP reduces the need for multiple internet subscriptions.

Types of NAT

NAT comes in different flavors, each with unique behaviors. Let’s break them down with examples and diagrams I created to make it crystal clear!

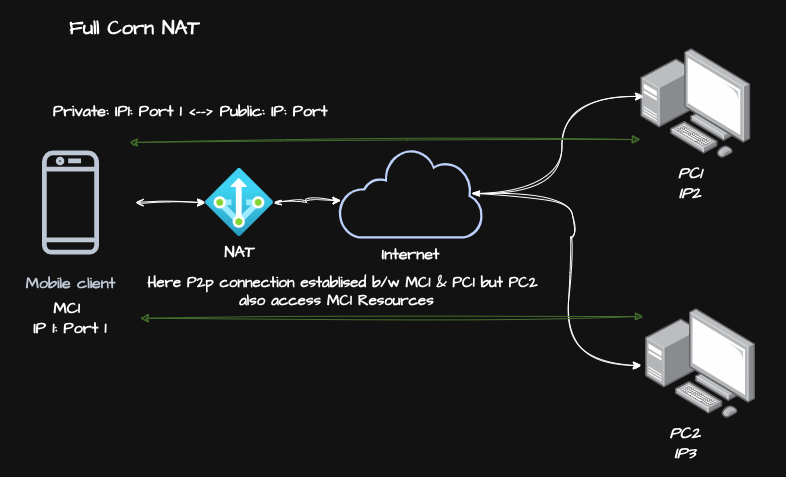

1. Full Cone NAT

In Full Cone NAT, once a device (like a mobile client) sends an outbound connection, any external device can send packets back to it using the same public IP and port.

- How It Works: A mobile client (MC1) with a private IP and port establishes a connection. The NAT maps this to a public IP and port, allowing PCs (PC1, PC2) to connect back.

- Diagram Insight: The connection is open for both PC1 and PC2 to access MC1 resources.

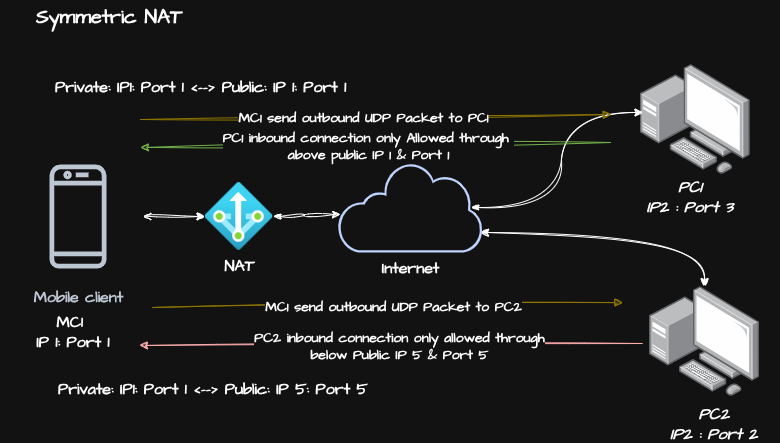

2. Symmetric NAT

Symmetric NAT assigns a unique public IP and port for each outbound connection, even to the same destination. Only the specific external device that received the outbound packet can send data back.

- How It Works: MC1 sends UDP packets to PC1 and PC2. Each connection gets a different public port (e.g., Port 1 for PC1, Port 5 for PC2). Only PC1 can respond via Port 1, and PC2 via Port 5.

- Diagram Insight: Inbound connections are restricted to the exact public IP and port pair used outbound.

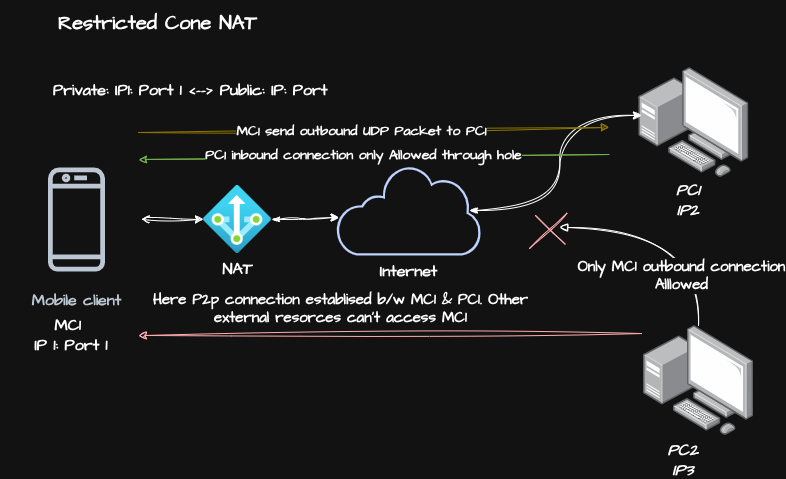

3. Restricted Cone NAT

In Restricted Cone NAT, an external device can send packets to the internal device only if the internal device has sent a packet to it first. Other external devices cannot initiate a connection.

- How It Works: MC1 sends a packet to PC1, opening a “hole” for PC1 to respond. However, PC2 or other external resources cannot access MC1 unless MC1 initiates contact.

- Diagram Insight: The red “X” shows blocked connections from uninitiated external devices.

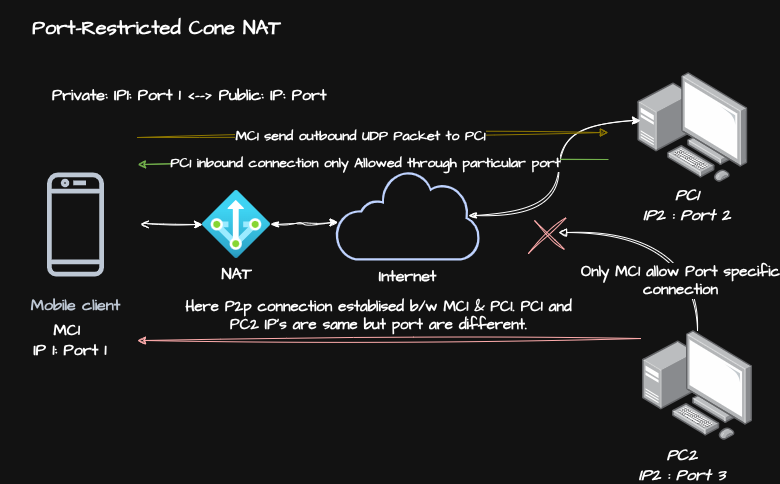

4. Port-Restricted Cone NAT

This is similar to Restricted Cone NAT but adds a port restriction. An external device can send packets only if the internal device sent a packet to that specific IP and port pair.

- How It Works: MC1 connects to PC1 and PC2 with the same public IP but different ports. Only the exact port (e.g., Port 2 for PC1) allows inbound traffic.

- Diagram Insight: The connection is limited to the specific port established during the outbound packet.

Conclusion

Understanding NAT and its types is key to managing network traffic effectively. Whether you’re setting up a home network or troubleshooting connectivity, knowing how Full Cone, Symmetric, Restricted Cone, and Port-Restricted Cone NAT work can save you a lot of headaches. Use the diagrams to visualize these concepts, and feel free to experiment with your network setup! Happy networking!