NAT Traversal: A Visual Guide to UDP Hole Punching

I. Introduction: The Invisible Walls of the Internet

Ever found yourself trying to connect to a friend for a gaming session, a video call, or perhaps sharing files directly, only to be met with frustrating “connection failed” messages? Or have you marveled at how effortlessly modern applications seem to bridge the gap, connecting you directly to someone on the other side of the world? Chances are, in both scenarios, you’ve been interacting with the silent, often-invisible gatekeepers of our home networks: NATs (Network Address Translators).

At their core, NATs are essential devices, typically integrated into your home router, designed to solve a fundamental internet problem: the scarcity of unique public IP addresses. They allow multiple devices within your private home network to share a single public IP address, acting as a kind of digital switchboard. Beyond this, they also provide a crucial layer of security, shielding your internal devices from direct, unsolicited access from the vast and often-hostile public internet.

However, this security and efficiency come with a significant challenge for peer-to-peer (P2P) communication. By default, a NAT is a one-way street for incoming connections – it only permits traffic that is a response to an outgoing request initiated by one of your internal devices. Any attempt by an external device to initiate a connection directly to your computer? That’s typically met with a cold, silent block. This makes direct communication between two devices, both sitting behind their own NATs, incredibly difficult.

But don’t despair! Network engineers, being the clever problem-solvers they are, devised an ingenious workaround to this challenge: UDP Hole Punching. In this visual guide, we’ll strip away the complexity and demystify how two devices, even when hidden behind their respective NATs, can deftly navigate these “invisible walls” to find each other and establish a seamless, direct connection. Get ready to understand the magic that underpins much of your online world!

II. NATs: The Gatekeepers (A Quick Primer)

At its heart, a Network Address Translator (NAT) is the crucial component, typically built into your home or office router, that acts as a traffic controller between your private local network and the vast public internet. Think of it as a security guard and a shrewd accountant rolled into one.

Its primary job is two-fold:

IP Address Sharing: It allows multiple devices within your private network (all with private, non-routable IP addresses like 192.168.1.x) to share a single, public IP address assigned by your Internet Service Provider (ISP). This conserves the dwindling pool of public IPv4 addresses.

Basic Security: By default, the NAT keeps your internal network hidden from the internet. When a device inside your network initiates an outbound connection (like opening a webpage), the NAT intercepts the packet. It then translates your device’s private IP and port into its own public IP and a unique, dynamically chosen public port. As you can see in our initial setup diagrams, this is where the NAT assigns an address like NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_STUN for your outgoing traffic.

III. Finding Ourselves: The Role of the STUN Server

Now we understand that NATs are protective, blocking direct incoming connections. This creates a new problem for our two friends, Alice and Bob, who both reside behind their own NATs: how do they even know what their own public internet address looks like? They can only see their private, internal IP addresses. They need a way to see themselves from the internet’s perspective.

This is where a STUN (Session Traversal Utilities for NAT) Server comes to the rescue. A STUN server is a publicly accessible server whose sole purpose is to help a device behind a NAT discover its public IP address and the specific port mapping its NAT assigns to its outgoing connections. Think of it as a friendly echo service on the internet that tells you, “This is how the world sees you!”

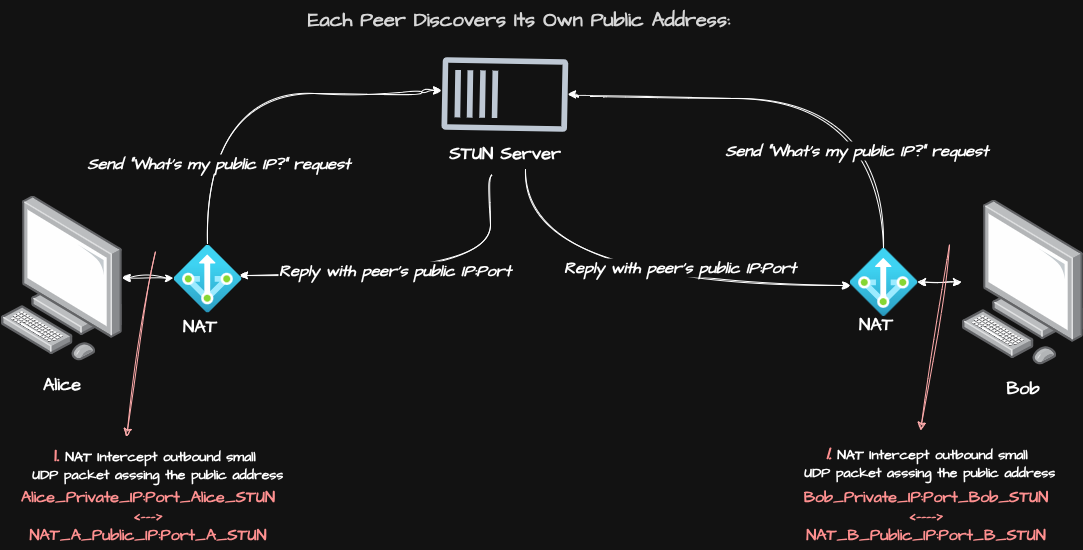

Let’s look at how this crucial first step works for both Alice and Bob, as shown in the diagram above:

-

1. Sending the Inquiry: Both Alice’s and Bob’s clients initiate a small UDP packet, a simple “What’s my public IP and port?” request, directed towards the STUN server. From their respective networks, these are standard outbound connections.

-

2. NAT’s Translation & Observation: When Alice’s request leaves her network, her NAT (NAT A) intercepts it. As we discussed, NAT A translates Alice’s private IP and port into a unique public IP and port (e.g.,

NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_STUN) for this specific outgoing request. The STUN server, being on the public internet, observes this public source address. -

3. The Echoed Reply: The STUN server then replies to Alice, sending a response back to the public IP and port from which it received the request (

NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_STUN). This reply includes that very public IP and port in its payload. -

4. Self-Discovery: Alice’s client receives this reply and now definitively knows her public IP address and the port her NAT assigned for her outgoing traffic. Bob goes through the exact same process with his NAT and the STUN server, learning his own unique public address (

NAT_B_Public_IP:Port_B_STUN).

IV. Exchanging Information: Who’s Where?

With both Alice and Bob now aware of their respective public internet addresses, the next crucial step is for them to share this information with each other. Think of it like exchanging phone numbers before you can call someone. This process is often referred to as signaling.

While a dedicated signaling server could be used, in the context of STUN and techniques like hole punching, the same STUN server (or a similar public server, sometimes called a TURN server or simply a relay server with added STUN capabilities) often plays a dual role. It not only helps with public address discovery but also facilitates this initial exchange of information.

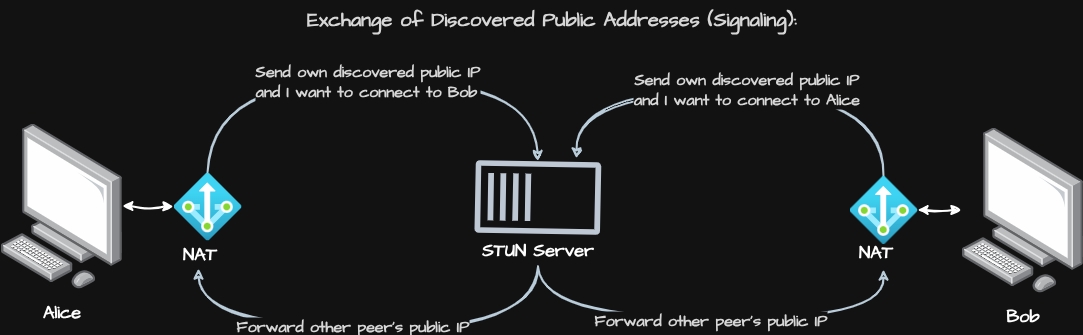

Looking at the diagram above, here’s how Alice and Bob get to know each other’s public “internet location”:

-

1. Alice’s Intent and Public Address: Alice’s establishes a connection (or uses the existing one from the STUN request) to the STUN/Relay server. She sends a message that essentially says, “Hey, STUN server, my public address is

NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_STUN, and I’m trying to connect to Bob.” -

2. Bob’s Intent and Public Address: Simultaneously or around the same time. He connects to the STUN/Relay server and sends a message stating, “My public address is

NAT_B_Public_IP:Port_B_STUN, and I want to connect to Alice.” -

3. The Forwarding Service: The STUN/Relay server, acting as a trusted intermediary, receives these messages. Recognizing that both Alice and Bob are trying to connect to each other, it then forwards the crucial information:

-

It sends Alice’s public IP and port (

NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_STUN) to Bob. -

It sends Bob’s public IP and port (

NAT_B_Public_IP:Port_B_STUN) to Alice.

V. The “Hole Punch” Moment: Making the Connection

Now, the stage is set. Alice knows Bob’s public internet address, and Bob knows Alice’s. They have each other’s “coordinates” as seen by the outside world. The brilliant trick of UDP Hole Punching lies in leveraging the very mechanism NATs use to provide security: the creation of temporary mappings for outgoing connections.

Remember how a NAT creates an internal mapping when you initiate traffic outwards? It opens a temporary “channel” for responses from that specific destination. The “hole punch” cleverly exploits this.

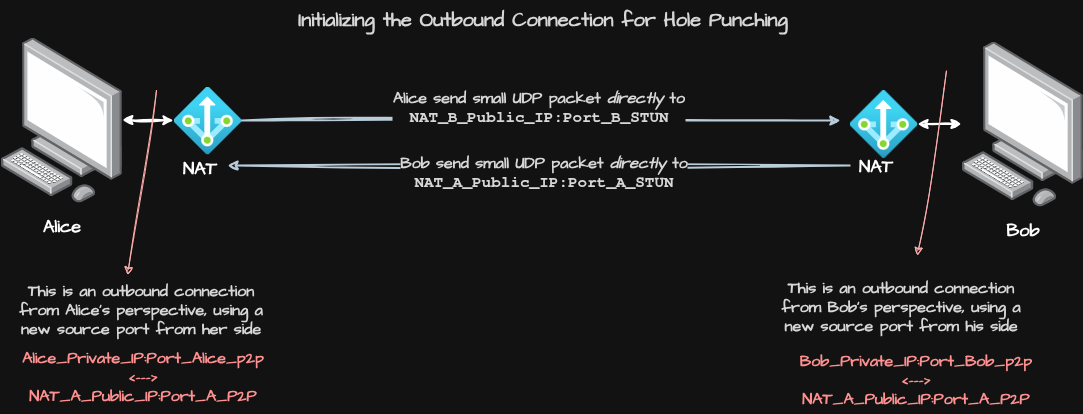

As illustrated in the diagram above, this is what happens:

-

1. The Simultaneous Outbound Send:

-

Alice’s Action: Alice’s Iroh client immediately sends a small UDP packet directly to Bob’s discovered public address (

NAT_B_Public_IP:Port_B_STUN). From Alice’s perspective, this is just another outbound connection initiated by her. Her NAT (NAT A) intercepts this packet and, for this new outgoing connection (aimed at the other peer), it assigns another specific public IP and port (e.g.,NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_P2P). This creates a temporary mapping:Alice_Private_IP:Port_Alice_P2P <-> NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_P2P. -

Bob’s Action: At virtually the same instant, Bob’s Iroh client performs the exact same action: he sends a small UDP packet directly to Alice’s discovered public address (

NAT_A_Public_IP:Port_A_STUN). Likewise, his NAT (NAT B) assigns a new public IP and port for this outbound connection (e.g.,NAT_B_Public_IP:Port_B_P2P) and creates its own temporary mapping:Bob_Private_IP:Port_Bob_P2P <-> NAT_B_Public_IP:Port_B_P2P.

-

-

2. The “Hole” is Punched:

-

When Alice’s packet arrives at

NAT_B_Public_IP:Port_B_STUN(which is Bob’s NAT), NAT B receives an incoming packet from Alice. Critically, because Bob just sent an outgoing packet to Alice’s address, NAT B sees this incoming packet as a “response” to Bob’s recent outbound probe. It recognizes the pattern and, thanks to the temporary mapping it just created, allows the packet to pass through to Bob’s private address. -

The exact same process happens in reverse when Bob’s packet arrives at Alice’s NAT.

-

VI. Direct Connection Achieved!

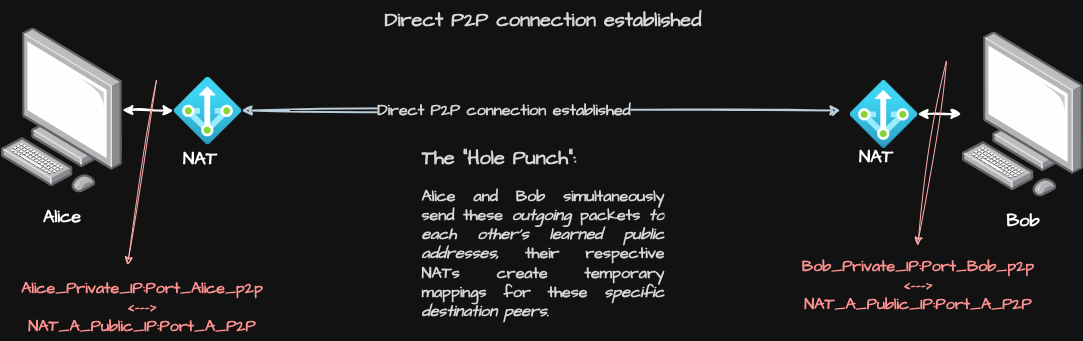

With the “holes” successfully punched in both Alice’s and Bob’s NATs, the moment of truth arrives! The temporary mappings created by their simultaneous outgoing packets now allow subsequent incoming packets to pass directly through each NAT.

As visually represented in the diagram above, Alice and Bob can now communicate directly with each other. Their data packets no longer need to be relayed through a third-party server. They flow straight from one peer’s public address to the other’s, passing right through the previously restrictive NATs.

This direct connection is the ultimate goal of NAT traversal techniques like UDP Hole Punching, and it brings significant advantages:

-

Lower Latency: Without an intermediary server, data travels the most direct path possible, leading to faster response times crucial for interactive applications like online gaming and video calls.

-

Higher Throughput: Removing the relay bottleneck allows for greater data transfer speeds, which is ideal for large file sharing or high-definition streaming.

-

Reduced Reliance on Relays: While relay servers are essential fallbacks, successfully establishing direct connections reduces the load and cost on these shared resources, making peer-to-peer systems more scalable and robust.

This direct line marks a seamless and efficient pathway for Alice and Bob to interact, truly unlocking the power of peer-to-peer communication!

VII. Why UDP? A Key Ingredient

Why is this technique specifically “UDP Hole Punching” and not TCP? The choice of UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is crucial because of its connectionless nature.

Unlike TCP, which requires a multi-step handshake to establish a formal connection before data can be sent, UDP is like sending a postcard: you simply address and send the packet. This “fire and forget” characteristic is essential. When Alice and Bob simultaneously send their “punch” packets, they don’t need to wait for a handshake. They just send. This unburdened, one-way sending is exactly what’s needed to trigger the NATs to open those temporary mappings. If they tried TCP, the handshake would fail because no “hole” exists for the initial replies.

Thus, UDP’s lightweight, connectionless approach is the indispensable ingredient that allows those crucial “punch” packets to successfully create a direct path.

VIII. Limitations and When It Doesn’t Work

While remarkably effective, UDP Hole Punching isn’t a silver bullet. Its success can depend on the specific type of NAT and firewall in place:

Symmetric NATs: These are the trickiest. Unlike other NAT types, a Symmetric NAT assigns a new, unpredictable public port for every new destination connection. This means the port used for the initial STUN request might differ from the port used for the hole-punching attempt, making it difficult for the other peer’s packet to find the correct “hole.”

Strict Firewalls: Some network configurations, especially in corporate or very secure environments, employ firewalls that are too restrictive for hole punching to succeed.

In these challenging scenarios, peer-to-peer applications typically fall back to using Relay Servers. While less direct and potentially slower, relays ensure connectivity when direct hole-punched paths aren’t possible, guaranteeing communication even in the most restrictive network environments.

IX. Conclusion

We’ve now journeyed through the intricate world of Network Address Translators and witnessed a truly ingenious solution to their limitations. From starting behind the “invisible walls” of NATs, we’ve seen how devices can leverage STUN servers for self-discovery, exchange their public addresses, and finally, execute the brilliant maneuver of UDP Hole Punching.

This technique, powered by UDP’s connectionless nature, is far more than just a networking trick. It is a fundamental enabler for countless modern applications we rely on daily – from the seamless voice chat in your online game and the smooth video stream of your conference call, to decentralized file sharing and various other peer-to-peer services.

The next time your favorite P2P application connects instantly, remember the silent, clever dance of packets, NATs, and the humble STUN server. You’ll now understand the “hole” story behind how your devices found each other directly, unlocking the true potential of connection on the internet.